A study released in Trends in Ecology & Evolution today reveals an intriguing relationship between elevated testicle temperature and the development of potent anti-cancer genes in elephants.

The research, led by Professor Fritz Vollrath, Chairman of Save the Elephants, suggests that the absence of testicular descent in elephants may have led to the emergence of multiple anti-cancer genes, which protect their temperature-sensitive sperm production.

This groundbreaking hypothesis opens up an exciting avenue for cancer researchers, potentially providing valuable insights into understanding how cells respond to DNA damage in humans.

Despite their large size and a higher number of somatic cell divisions, which typically increase the risk of cancer, elephants defy expectations. This phenomenon, known as Peto’s Paradox, was first observed by renowned Oxford epidemiologist Richard Peto, who noted that elephants and whales exhibit surprising resistance to cancer development.

Recent scientific advancements have shed light on the crucial role of elephants in unraveling this fascinating puzzle of cancer mitigation. A key factor is the connection between a genetic marker called the TP53 gene and its protein product, p53. P53 identifies and neutralizes damaged DNA during cell divisions, thereby preventing the spread of mutations.

Remarkably, elephants possess 20 copies of the TP53 gene, while all other known animals, including humans, have only one copy. This raises the question: Why have elephants evolved this seemingly magical defense mechanism against cancer when other species have not?

The study emphasizes that selection on somatic cells, which comprise the body’s organs and tissues, is relatively weak and slow due to the complex mix of healthy and potentially harmful cells. Moreover, evolutionary changes that occur in older age, after most offspring have been produced, tend to proceed gradually. In contrast, selection on germ cells, such as sperm and eggs, is significantly stronger and faster because it directly impacts the survival of each individual cell.

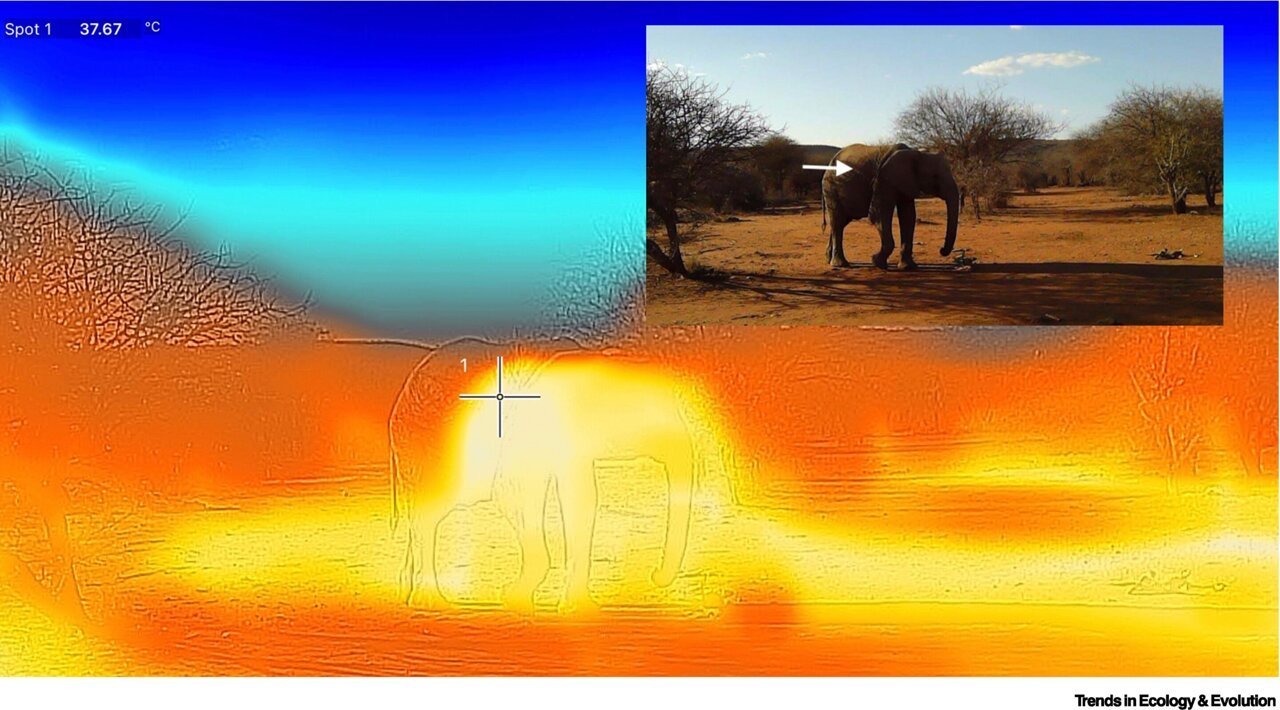

This brings us to the intriguing topic of testicle temperature. In mammals, the production of healthy sperm relies on the testes being several degrees cooler than the body temperature. Consequently, the descent of testicles into a scrotum plays a vital role in cooling them as maturity approaches. However, elephants lack the genes responsible for this descent, causing their testicles to remain inside their bodies even in mature bulls, subjecting them to elevated temperatures.

Considering elephants’ vulnerability to climatic challenges due to their large size, unfavorable surface ratio, thick skin, and heat exchange mechanisms centered on blood flow in the ear flaps, their body temperatures can rise to levels that are detrimental to mammalian metabolism and sperm production.

According to the paradigm proposed by this study, the proliferation of TP53 genes in elephants would not have primarily evolved to combat cancer but rather to support DNA stabilization in the spermatogonia, ensuring the production of robust spermatozoa and safeguarding the germ line. Nevertheless, this diversification of p53 proteins also offers protective benefits against DNA damage and mutations in somatic cell lines, thereby providing additional advantages related to cancer and aging, areas where p53 is known to play a prominent role.

Professor Vollrath, commenting on the research, says, “Elephants provide us with a unique system to study the evolution of a robust defense mechanism against DNA damage and explore the intricate details of the p53 complex in our own battle against cancer and conditions like aging. Novel insights in this field are always important, but especially now that overheating is becoming an increasingly significant issue for humans as well.”