The chickpea, with its rich flavor and abundant nutrients, has been a staple in diets and cultures for thousands of years. However, the origins and spread of this versatile legume across the Middle East, South Asia, Ethiopia, and the western Mediterranean have long been a mystery.

A recent study titled “Historical routes for diversification of domesticated chickpea inferred from landrace genomics” published in Molecular Biology and Evolution sheds light on the genetic heritage of chickpeas and the impact of human migration and trade on their diversification.

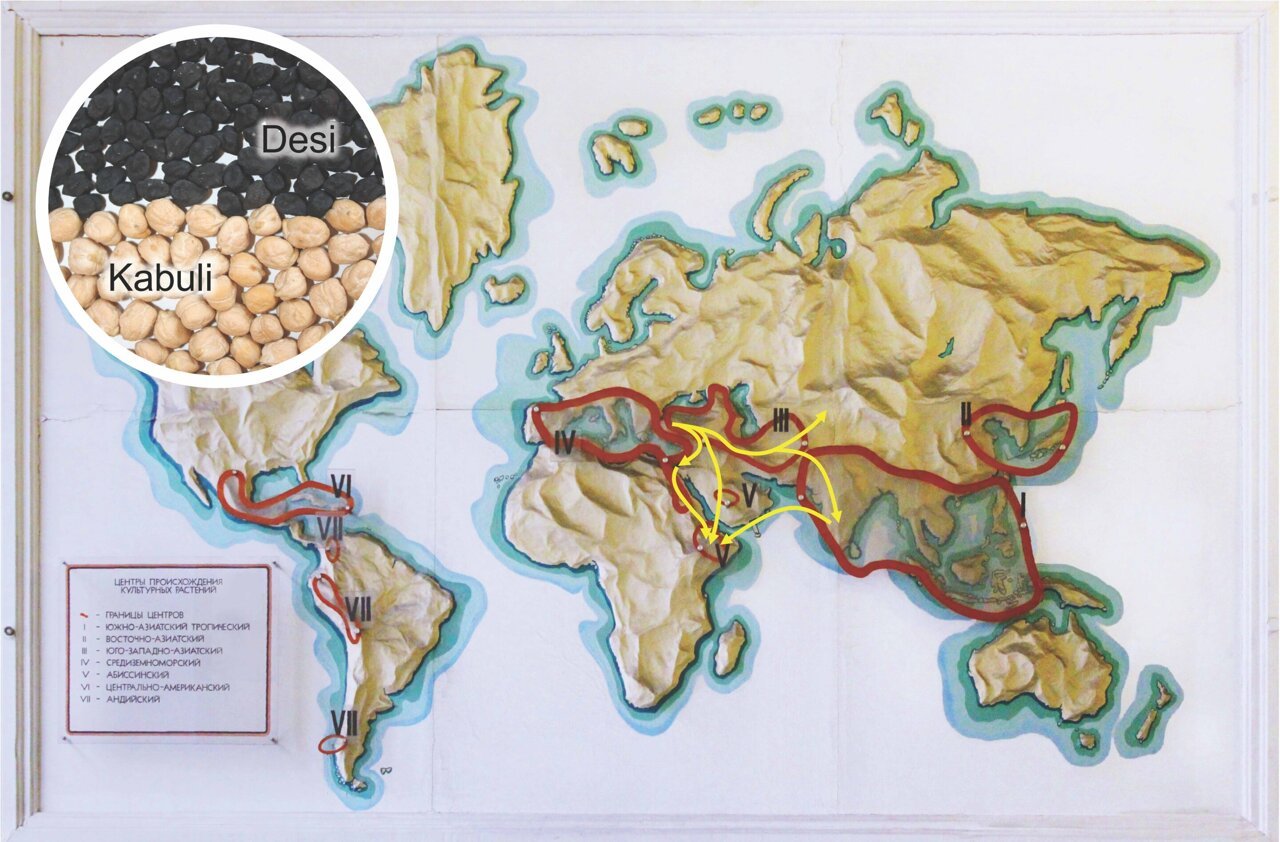

Led by Anna Igolkina from Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, Eric von Wettberg from the University of Vermont, and Sergey Nuzhdin from the University of Southern California, the study analyzed genetic data from over 400 chickpea specimens collected in the 1920s and 1930s. These specimens included two main types of chickpeas, desi and kabuli, which differ in color and size but lack clear geographic or genetic boundaries.

The samples were obtained from nine geographic regions: northern Mediterranean, southern Mediterranean, Turkey, Lebanon, Ethiopia, the Black Sea, western Uzbekistan, eastern Uzbekistan, and India. To analyze the data, the researchers developed two new models called popdisp (population dispersals) and migadmi (migrations and admixtures).

Using the popdisp model, the researchers examined how chickpeas spread within each region. They compared two scenarios: one where chickpeas dispersed along possible historic trade routes, and another where dispersal occurred in a linear fashion, disregarding geographic barriers.

Surprisingly, the results showed that genetic similarity among chickpea landraces in different regions was more influenced by the costs of human movement rather than linear distance. This suggests that chickpea spread within each region predominantly occurred along trade routes, rather than simple diffusion.

Using the migadmi model, the scientists aimed to uncover the origin of the Ethiopian desi population, which has a unique flavor combining the tartness of Indian black desi chickpeas with a hint of sweetness. Previous studies proposed two possible origins: an Indian origin based on morphological similarities or a Middle Eastern origin due to human migration from western Eurasia to East Africa around 4,500 years ago. The study found evidence supporting both scenarios, revealing that Ethiopian chickpeas have ancestry from Indian, Lebanese, and Black Sea source populations.

The study also challenged the linguistic suggestion that the kabuli type originated in Central Asia and was named after Kabul city. Instead, the results indicated a possible origin of the kabuli type from a local desi chickpea population in Turkey.

While this research provides valuable insights into the natural history of chickpeas and their connection to human trade routes and migrations, its implications extend beyond this legume. The development of the popdisp and migadmi models offers new tools for studying complex migration patterns, which can be applied to other species. These models, based on compositional data analysis, can be extended to analyze genetic markers in other organisms, including structural variants.

Overall, this study deepens our understanding of chickpea history while paving the way for further investigations into migration patterns in various species, both human-associated and natural.

Source: SMBE Journals (Molecular Biology and Evolution and Genome Biology and Evolution)